Ancient Mysteries Unfold: The Surprising Genetic Story of China’s Desert Mummies

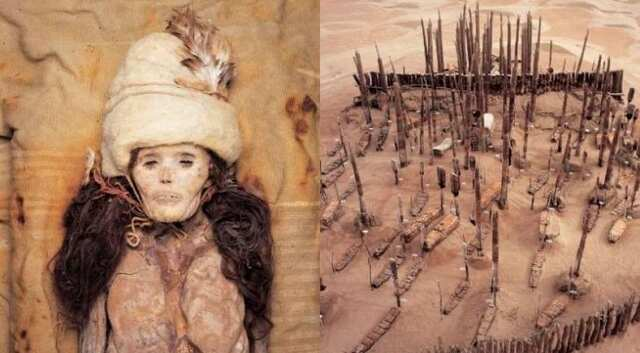

The discovery of hundreds of mummified bodies in the Tarim Basin of Xinjiang, northwestern China, has intrigued scientists and historians alike. These mummies, dating back approximately 4,000 years and found mostly in the 1990s, are remarkably preserved—complete with visible facial features and hair color. Initially, their Western appearances, woolen clothing, and dietary remnants led researchers to believe they were either nomadic herders from West Asia or farmers from Central Asia.

However, a groundbreaking study conducted by an international team of researchers from China, Europe, and the United States has shed new light on the origins of these enigmatic mummies. By sequencing the genomes of 13 mummies for the first time, the study reveals that these individuals were not migrants but descendants of a local population that dates back to the Ice Age.

Christina Warinner, an associate professor of anthropology at Harvard University, emphasized the significance of these findings. “The mummies are not only extraordinarily preserved but also found in a unique archaeological context, displaying a mix of cultural elements,” she explained. “Our genetic analysis strongly indicates that they were a highly isolated local group, which nonetheless adopted various technologies and ideas from neighboring herder and farmer communities, creating a distinct cultural identity.”

This research also included DNA comparisons with older remains from the Dzungarian Basin in the northern part of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which date back between 4,800 to 5,000 years. Vagheesh Narasimhan, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin who specializes in Central Asian genetics, noted the significance of using ancient DNA to trace human migration and interaction patterns, particularly when other historical records are absent. Although not involved in the study, Narasimhan described the findings as “exciting.”

The study concluded that the Tarim Basin mummies show no genetic mixing with other contemporary groups. Instead, they appear to be direct descendants of a widespread Ice Age population that had largely vanished by around 10,000 years ago. Known as Ancient North Eurasians, this hunter-gatherer group’s genetic legacy persists only minimally in today’s global population, with the highest concentrations found in Indigenous Siberians and some Native American groups. The presence of these genetic traces in the Tarim Basin mummies, dating from such an ancient period, was completely unexpected.

This new genetic evidence provides a profound insight into the prehistoric movements and cultural developments of ancient Eurasian populations, redefining our understanding of these mysterious mummies buried in the Chinese desert.